If you have been watching the Vikings program on Netflix you may be wondering why the Vikings left Greenland. Now, a recent study reveals it was likely because of drought. Here's the story from SCIENCE magazine.

Greenland’s Vikings may have vanished because they ran out of water

New study spotlights drought, rather than temperature or other reasons, as key to Norse disappearance

23 MAR 2022 BY COLIN BARRAS SCIENCE

For more than 450 years, Norse settlers from Scandinavia lived—sometimes even thrived—in southern Greenland. Then, they vanished. Their mysterious disappearance in the 14th century has been linked to everything from plummeting temperatures and poor land management to plague and pirate raids. Now, researchers have discovered an additional factor that might have helped seal the settlers’ fate: drought.

The Vikings raided, traded, and eventually formed Norse settlements throughout northwestern Europe, including in Iceland. According to Icelandic legend, an explorer named Erik the Red then sailed west around 985 C.E. and established two settlements in southern Greenland. At its peak, about 3000 Norse farmers raised cattle, sheep, and goats on the island.

USING BIOCHEMISTRY OF BACTERIA

In the new study, Boyang Zhao, a paleoclimatologist at the University of Massachusetts, Amherst, and colleagues analyzed mud from the bottom of a lake in southern Greenland for clues about the climate Norse settlers experienced during their time there, between about 985 and 1450 C.E. The lake lies within one of the two settlements (the Eastern Settlement), near a cluster of stone ruins that were once Norse homes and cow sheds.

Last year, the team showed the biochemistry of bacteria in the lake changes in response to temperature. For the new study, they extracted the remains of long-dead microbes from the layers of mud on the lake bed, which they dated with radiocarbon. By tracking changes in bacterial chemistry through time, they reconstructed past temperatures.

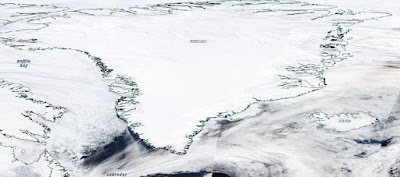

(Image: Greenland as seen by the NOAA/NASA Suomi NPP satellite on March 23, 2022. Credit: NOAA/NASA Worldview)

NO LONG TERM COOLING TREND FOUND DURING VIKING OCCUPATION

Although temperatures fluctuated during the period of Norse occupation, the researchers found no long-term cooling trend. “When I saw those temperature records I got pretty surprised,” Zhao says, considering the widely held view that falling temperatures made tending livestock challenging and contributed to the demise of the settlement.

HYDROGEN ISOTOPES CLUE IN WATER AVAILABILITY

The data on water availability told a different story. To examine this feature, the team looked at hydrogen isotopes in the remains of plants buried in the lake mud. When plants lose water to evaporation in dry weather, their leaves become enriched in a heavy hydrogen isotope, deuterium. By measuring the deuterium content of leaf remains from layers in the lake mud, the researchers found that southern Greenland’s climate became progressively drier during the Norse period, as they report today in Science Advances. With droughts more common, the Norse would have been unable to grow enough grass to keep their livestock from starving during the long, cold winters, Zhao says.

It’s certainly believable that the Norse had to deal with drought, says Thomas McGovern, an archaeologist at Hunter College. Excavations at Norse farms have uncovered evidence of irrigation channels to capture water and spread it over a wide area, he notes.

Modern farmers in Greenland also deal with water shortages, says Zhao, who talked to locals while in the field. “I asked them: What’s the most important challenge for you today? They said if they don’t get enough rain in the summer they don’t get enough grass to feed their animals.”

RECENT DROUGHTS

Several severe droughts have struck Greenland in recent years. “Around 2015 it was very dry—we had rain in June and then the next came in August,” says Elna Jensen, who farms land near Narsaq, Greenland, close to the lake Zhao’s team studied.

But Norse and modern farming are different, cautions Christian Madsen, deputy director of the Greenland National Museum and Archives. For instance, many modern farmers have drained and fertilized their land to improve productivity, but this leaves the land more vulnerable to the effects of drought.

VIDEO: https://youtu.be/6kmyq3ZUTFg

(video: These animations show the cumulative change in Greenland Ice Sheet thickness and the melting ice sheet's contribution to global sea level from 1992 to 2018, with projections through 2100. The projections were drawn from the 5th Assessment Report (AR5) by the United Nation's Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC). IMBIE, or the Ice Sheet Mass Balance Inter-comparison Exercise, is an international collaboration between polar scientists from 50 scientific institutions supported by the European Space Agency and NASA. Credit: University of Leeds/Planetary Visions/Technical University of Denmark)

VIKINGS ADAPTED TO CLIMATE CHANGE

It’s also important to appreciate that the Norse did attempt to adapt to the changing environment on Greenland, McGovern says. Archaeological evidence shows they began to consume more marine food, including seal meat, as farming became harder.

They vanished anyway, and McGovern argues social factors may have played a key role, too. The Norse undertook long and dangerous voyages to the waters off northwest Greenland where they hunted walruses for ivory to sell on the European market. Ivory was a source of wealth and power for local elites, but by taking a chunk of the working population away from food production as conditions deteriorated, walrus hunting may have helped doom the settlement.

No comments:

Post a Comment